Who was

William Warfield?

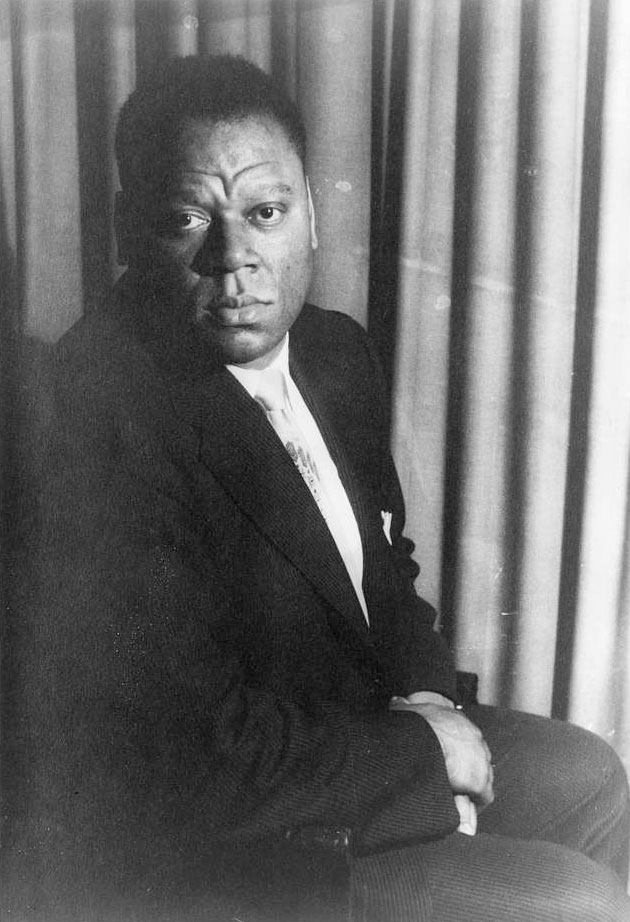

Acclaimed throughout the world as one of the great vocal artists of our time, William Warfield was a star in every field open to a singer’s art.

Recital Debut

His recital debut in New York’s famous Town Hall of March 19, 1950 put this artist overnight into the front ranks of concert artists. That historic debut was celebrated March 24, 1975 in Carnegie Hall when, for its 25th anniversary, William Warfield gave a recital for the benefit of the Duke Ellington Center.

Since Warfield’s remarkable debut, his career flourished unabated in a wide assortment of memorable achievements. In 1950, he was invited by the Australian Broadcasting Commission to tour that continent for 35 concerts June through September, including solo performances with their five leading symphony orchestras. While that tour was still proceeding, his manager back in New York had signed a contract with MGM for Warfield to play the featured role in the most recent version of the great Edna Ferber-Jerome Kern musical Showboat as Joe the dock hand.

The Beginning

This man, who was destined to become one of America’s greats, was born in West Helene, Arkansas, on January 22, 1920, the eldest of five sons. Both of his parents, Robert and Bertha McCamery Warfield, were the children of African American slaves. While still a small child, his father, Robert E. Warfield, moved his family north to Rochester, New York in order to seek better educational and employment opportunities.

William graduated from Rochester city schools and earned a New York state cosmetology license. During his senior high school year, he won the National Music Educators League Competition and a full scholarship to any American music school of his choice. William chose the Eastman School of Music, where he received his bachelor’s (1942) and master’s degree after four interim years in the military intelligence division of the Army (1946).

After military service, Warfield was engaged for singing lead in the national touring company of the Broadway hit Call Me Mister. It is interesting to note that three other members of that same “second company” cast went on as did Warfield to ultimate success and fame in the entertainment world: comedian Buddy Hackett, the romantic comedy lead Carl Reiner, and the famous choreographer/dancer/director Robert Fosse.

After he started working in his professional field, William recounted painful memories of racial slurs, closed doors and impossible barriers. He regularly experienced racial discrimination. He found the opportunities for an African American male opera singer remained too limited, whereas the concert tours and popular music scenes still presented him with ample means of professional fulfillment. “Opera wasn’t ready for me, or any black male …But it never occurred to me to give up.”

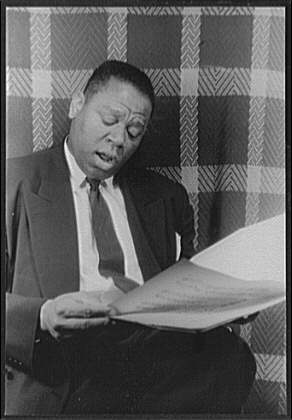

Through his persistence and great vocal talent, William’s career expanded and deepened–countless concerts, recitals, soloist appearances with symphony orchestras and their big-name maestri, even performances as non-singing narrator…with many impressive honors and awards in recognition of William Warfield for his important contribution in The Arts. Among his frequent appearances in foreign countries, this artist has made six separate tours for the US Department of State, more than any other American solo artist.

Through the years, critics have commented that William Warfield’s superiority as recitalist stems from his unusual ability as an actor, which he has proven often in singing roles as well as those merely spoken. His most famous role is the title role in George Gershwin’s opera Porgy and Bess. A memorable and important segment of Warfield’s professional life was in his performance in 1957 and 59 on NBC-TV’s Hallmark Hall of Fame production of Marc Connely’s The Green Pastures, in his starring role as “De Lawd.”

Recognition

William was known worldwide for his work as a soloist, recitalist, actor, narrator and activist and received numerous honors and awards.

He was acclaimed throughout the world as one of the great vocal artists of our time, and was a star in every field open to a singer’s art. William was one of the world leading experts on Negro Spirituals and German Lieder; received numerous honorary doctorates including: Doctor of Laws from the University of Arkansas in 1972; a Doctorate for his “Contributions in the Arts” in 1977 from Lafayette University; in 1982 from Boston University; in 1983 a “Doctor of Humane Letters” from Augustana College, Illinois; and in 1984 from James Milliken University, Illinois.

In March 1984, he was the winner of a Grammy in the “Spoken Word” category for his outstanding narration of Aaron Copeland’s A Lincoln Portrait accompanied by the Eastman Philharmonia Orchestra.

Since 1975, when he accepted his appointment as Professor of Music at the University of Illinois (Champaign-Urbana Campus), Warfield was able to continue outside concert performances along with master classes at many institutions of learning. In 1989, he began touring with the Jim Cullum Jazz Band (JCMB) as the narrator in the band’s concert presentation of Porgy and Bess. In 1996, live presentations of Showboat and, in 1997, Harlem Rhapsody were added to the JCJB/Warfield touring schedule. In 1999 Warfield joined baritones Robert Sims and Benjamin Matthews in a trio by the name of “Three Generations”. and toured the United States giving full concerts of African-American spirituals and folk songs until his death.

In 1991, William published his uncommonly personal memoir, My Music & My Life. In 1994 he joined the faculty of at Northwestern University’s School of Music as a professor doing what he loved—teaching young voice students, until his death. In a 2000 interview he commented: “Why should I quit the stage, anyway? Age has nothing to do with anything. As long as this old voice holds out and I still enjoy it, I’ll never stop singing”.

Warfield died at age 82 August 25, 2002, in Chicago from complications from a broken neck suffered in a fall. He is buried in Mt. Hope Cemetery, Rochester NY. Many of his family continue to live in Rochester NY.

Biography from Riverwalk.org and other sources.

More about the William Warfield

William Warfield was an American concert bass-baritone singer known worldwide for his work as a soloist, recitalist, actor, and narrator. He broke down racial barriers throughout his entire career, opening doors for African American artists who came behind him.

William Warfield was born in West Helena, Ark., On January 22, 1920, the oldest of five sons of a Baptist minister and sharecropper. Both of his parents, Robert and Bertha McCamery Warfield, were the children of African American slaves.

At age five, his father, Robert E. Warfield, decided to move his family north in 1925 to Rochester, New York in order to seek better educational and employment opportunities.

Both parents were musically inclined, so William’s father encouraged his sons’ musical development with the purchase of an upright piano for the house. William studied both piano and organ, supporting his studies–and the family’s finances–with various part-time jobs. He also sang as a boy soprano in the youth choir at his father’s church. By the time he reached high school, Warfield’s voice had transitioned to baritone, its quality earning him numerous solos with the school choir. He began voice lessons with one of his high school teachers, who helped him prepare the Spiritual, “Deep River” by Harry T. Burleigh, for a school assembly program. The audience’s reception of the 16-year-old’s performance convinced him that he wanted to pursue a professional musical career. The following year, Warfield met soprano Dorothy Maynor after her recital at the Eastman Theater and asked her for her autograph. He later said that when she asked him about his plans for the future and he replied:

“I’m going to be a singer, like you,” I told her. She smiled as she completed her inscription on the photograph I had handed her. I watched her and reflected that she was as beautiful in person as she had sounded on stage. She was occupied with other guests in her dressing room, so I thanked her for the autograph and for the concert, and stumbled back out into the Rochester afternoon. When I looked down at her signature I was instantly elevated: Dorothy Maynor had written, “To a colleague.”

At the same time that Warfield continued his music studies and entered various scholarship competitions, he earned a New York state cosmetology license and graduated from high school. He was admitted as a voice student to the Eastman School of Music with a full scholarship. In addition to taking the regular musical course work–including foreign language studies, he participated in the community theater and was hired to play minor roles for the local radio station.

His original goal was to become a music teacher, partly because he did not have great confidence that a black singer could make a career in concert halls and opera. But some of the few who had — among them Marian Anderson and Paul Robeson — encouraged him to consider the stage his goal, and on their advice, he focused more on vocal and dramatic studies than on teaching.

William Warfield described how he grew up in an atmosphere free of discrimination and the virulent racism he encountered after he started working in his professional field. He recounted painful memories of racial slurs, closed doors and impossible barriers. He regularly experienced racial discrimination along with fellow tour performer, baritone William Marshall.

Warfield described their diverse reactions to the numerous instances of racial bigotry they and others in the Black community faced: “That was the climate that was always around us then. Neither William Marshall nor I were on the barricades of the movement–each of us, in our own way, worked out our commitment on a different kind of stage–but temperamentally you could say that Bill Marshall and Bill Warfield represented opposite extremes within our own band of the spectrum. He didn’t miss a single nuance of even unconscious racism. I shrugged it off; racism was going to be the racist’s handicap, not mine.”4

Warfield, in contrast, found the opportunities for an African American male opera singer remained too limited, whereas the concert tours and popular music scenes still presented him with ample means of professional fulfillment. One of his stops on the African tour was to Rhodesia, a country still governed at that time by its apartheid policies.

Warfield described the extraordinary arrangements made to accommodate his presence: As a black man I couldn’t even walk into a white post office to mail my letters. Because I would certainly have encountered problems just walking through a park and perhaps using the wrong water fountain, I was escorted by dignitaries or their deputies everywhere I went. It was all very white-gloves, but it was nonetheless clear: For all practical purposes, I was in the protective custody of the officials. It was as if I were hermetically sealed from the country and its problems. I could observe it, but I was protected from it.”

Opera wasn’t ready for me, or any black male. Hollywood was still wrestling with its own soul, and not ready to open up to African-American themes. Broadway, and the theater in general, was still struggling with the same issues. As I progressed along my career ladder I found a few rungs missing, and sometimes had to look for a foothold in the most improbable places.

But it never occurred to me to give up. What kept me going, I now realize, was that even though I often had no clear idea of how to get there, I always had a clear idea of where I was ultimately headed. I had the example of my heroes; they had proved it could be done. And I had the incentive of my art: I always knew that beyond the nightclubs and the films and the Broadway shows, my destiny lay in the sublime realm of classical music. So I usually found those other footholds where the rungs were missing–and I learned how to jump! (from his bio: My Music and My Life)

In 1952 Mr. Warfield undertook a long tour of ”Porgy and Bess” During the tour, he married his co-star and soprano Leontyne Price – the day before the cast left for Europe. The wedding took place at the Abyssinian Baptist Church, in Harlem, with the entire cast of ”Porgy and Bess” in attendance. The couple separated six years later (1958) and divorced 20 years later in 1972, but they remained on friendly terms and continued to collaborate.

In 1975, he accepted his appointment as Professor of Music at the University of Illinois (Champaign-Urbana Campus), in 1994 he joined the faculty of at Northwestern University as a professor until his death in 2002. He also gave master-classes at many institutions. He received several doctorates from universities for his gifts as an artist and teacher.

Warfield died at age 82 August 25, 2002, in Chicago from complications from a broken neck suffered in a fall. He is buried in Mt. Hope Cemetery.

He was one of the world leading experts on Negro Spirituals and German Lieder.

He was past President of the prestigious National Association of Negro Musicians (1985-1990).

In the course of a career that has spanned more than half a century, his incomparable voice and charismatic personality have electrified the stages of six continents and earned him the title of “America’s Musical Ambassador.”

He published his uncommonly personal memoir, {My Music & My Life,}

Critical opinion regards him as one of the great singer-actors of the 20th century.